Introduction

Pune has witnessed the construction of several aqueducts, cisterns, ornamental pools, ponds, and tanks throughout history, similar to many other places in India. Many of these water structures represent the traditional wisdom and efficient water management practices of our ancestors.

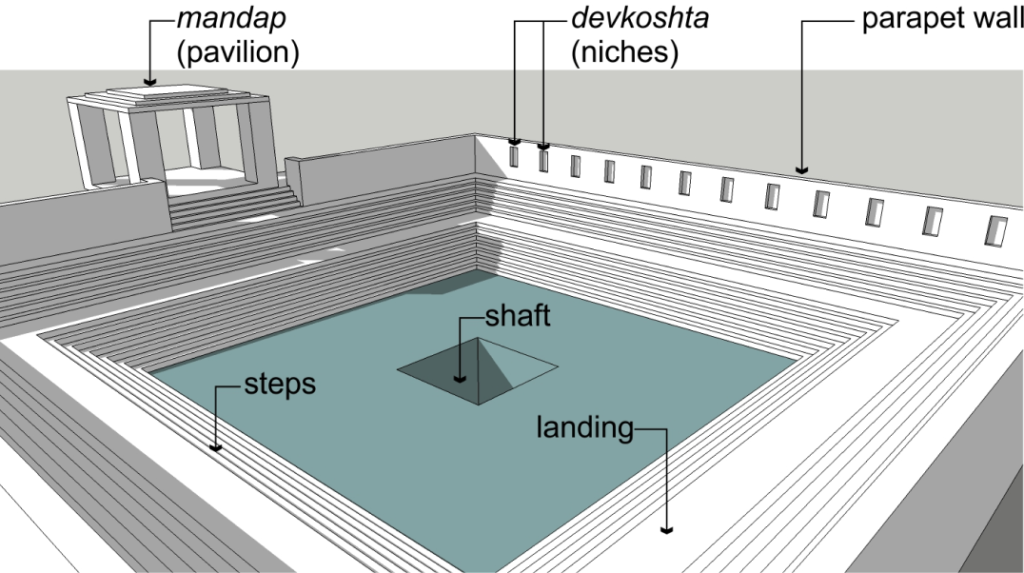

This photo essay narrates the story of one such traditional water structure known as barav, which is a stepped pond or a well. A typical barav consists of a shaft penetrating deep inside the earth to tap groundwater. A steep flight of steps surrounds the shaft, providing access to the people for fetching groundwater. Baravs may be square, rectangular, or octagonal in shape with a parapet wall along their perimeter. One or more pavilions known as mandaps are sometimes present along the sides of the baravs. The name ‘barav’ comes from a traditional unit of measurement called ‘bav’, equivalent to 1.5 metres. Additionally, baravs are also known by the names kund, jalmandavi, and pushkarini.

The religious idea of attaining spiritual merit by performing acts of charity motivated many rulers, traders, money lenders, and priests to patronize the construction of baravs for the common good of the society at different places in Maharashtra. They were built with the financial support of the patrons, but were owned and maintained by the entire community, often transcending the social divides, as understood from the ancient stone inscriptions that exist near them. They were not only utilitarian structures, but also meeting places for people, especially women fetching their daily water, as well as sacred structures for holy bathing as part of religious rituals.

Baravs found in Pune

Once upon a time, baravs were an inherent part of many settlements and temple precincts in Pune. A barav next to a shade-giving tree is a common sight in some of villages of Pune even today. Elsewhere, although baravs may have been destroyed over a period, their memory remains intact amongst the older generation of people. Interestingly, in the Junnar taluka (a block) a village itself is named as ‘Barav’ after an old barav which once existed there. In short, baravs were an inseparable part of many settlements.

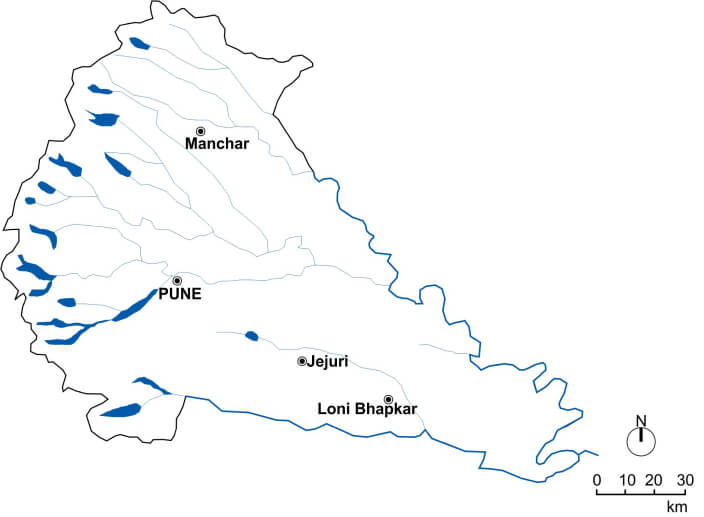

This story talks about two baravs which are more than 600 years old, built somewhere in the early 14th century. One of them is found at Manchar town in Ambegaon taluka and the other one is found at Loni Bhapkar village in Baramati taluka of Pune district. The barav at Manchar is still used by the people for bathing and swimming. The one at Loni Bhapkar is part of a temple complex and has religious significance. Although its waters have become unfit for domestic use over time, it is an excellent piece of architecture displaying artwork in basalt rock.

The barav at Manchar

The town of Manchar was once a small village during medieval times, located on the trade route connecting the historic towns of Paithan (famous for its sarees) and Junnar. The barav found in Manchar is a beautiful one located next to a small water course called as ‘Khardi Nala’. This barav is fed by a natural spring and contains ample water throughout the year.

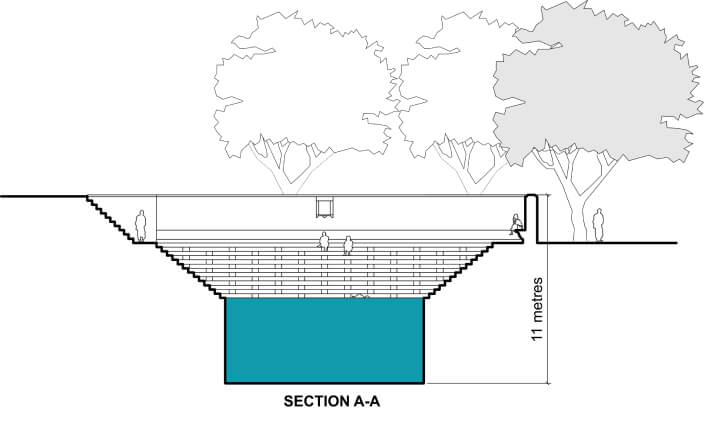

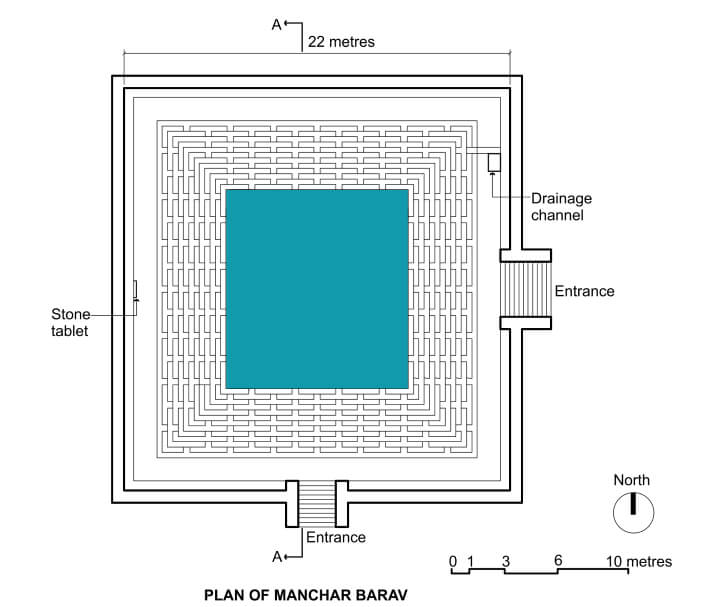

The barav at Manchar is nearly a square which tapers from a width of 22 metres on its topmost side to nearly half the length (11 m) at the bottom side. It has two entrances – one from the south and another from the east. After descending down from these two entrances, one reaches to an intermediate landing that has a raised seating platform.

Steps are a striking feature of this barav. Adjacent steps contain protruding stone blocks at regular intervals to counterbalance the thrust of the soil from behind. They also act as intermediate seating platforms, creating a beautiful rhythmic pattern, which highlights the aesthetic side of structural elements.

A stone inscription housed in the western parapet wall, narrates an interesting story about the construction of this barav. According to the Sanskrit inscription, Manichar (previous name of Manchar) was a beautiful village stationed in the hills of Amargiri. In Manichar, there lived an able, just, brave, and handsome person named Ladidev, who was the son of the village head (mentioned as pattelvarya). One night in his dream, Ladidev sees Mother Earth expressing her wish to permanently reside in his village. Waking up the next day, Ladidev recollects his dream and decides to build a barav at a suitable spot in the village where Mother Earth would permanently reside in the form of water. He thinks that the barav would also help in relieving the water stress conditions experienced by the villagers of Manchar due to frequent droughts. With these considerations, Ladidev initiates the construction of the barav on an auspicious day in the Shaka Samvat year 1266 (i.e. 1344 A.D.) (Ref: Mandake, G, 2003).

Today, the barav is popular amongst the people of Manchar as ‘angholichi barav’ (meaning barav used for bathing). Many adults and school-going kids assemble at the barav during early morning hours for bathing.

“We love swimming in this historical barav. It is always full with water, even in summer. We come here as early as 5 am and enjoy swimming until the afternoon sometimes. Applying soap and bathing in the barav is prohibited, so as to keep its water clean”

“We kids have competitions for jumping into the barav. Taking a dip into the barav is great fun. But now during times of Covid, police have put restrictions on the number of people bathing at a given time. So usually we come in groups not exceeding 10-15”

A small channel carries water from the barav into a kund, which is a small stepped pond located on its eastern side. Women assemble at this kund daily for washing clothes. Thus, while the barav becomes a social interaction space for men, the kund becomes an interactive space for women, who get a break from their daily routine and find a few leisure moments for chatting with each other while washing their clothes.

The barav at Loni Bhapkar

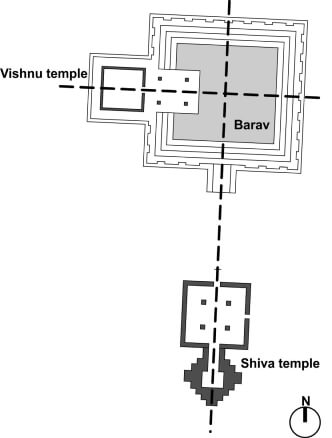

Loni Bhapkar village contains a beautiful barav built way back in the 14th century. The barav is part of a sacred precinct, originally containing temples of Shiva and Vishnu. Today, the original Shiva temple is in a dilapidated condition, while a new Dattatray temple has been built in place of the Vishnu temple. Interestingly, the barav is placed strategically at the focal point of the two temples, highlighting its significance and sacredness in the entire complex. Earlier, as part of religious rituals, people would take a bath in the barav before entering the temple. They believed that such ritualistic bathing washed away their sins and purified them before entering the sacred temple.

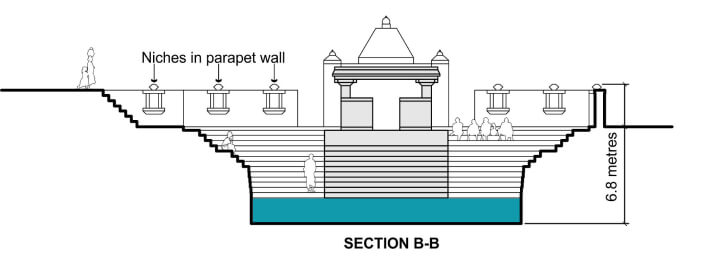

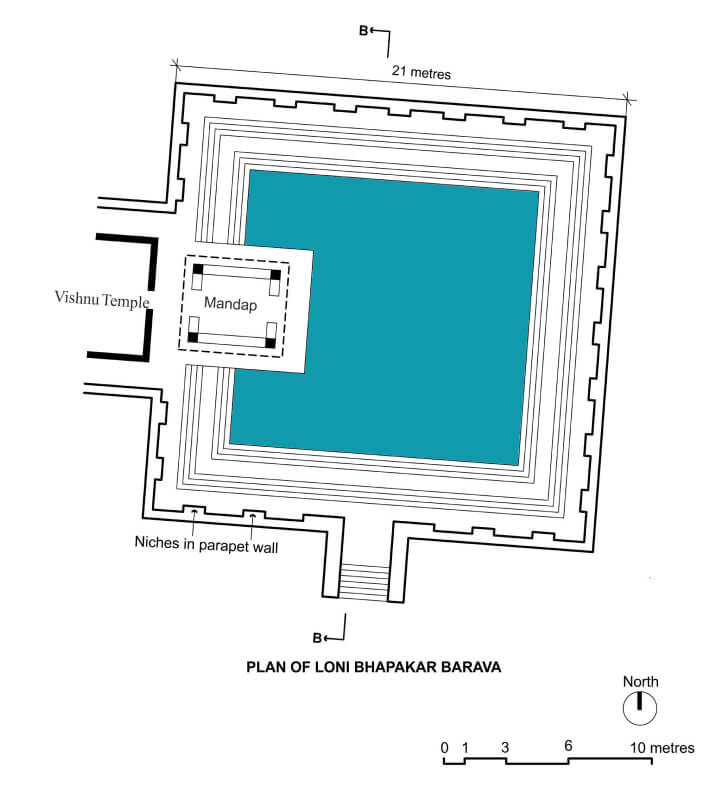

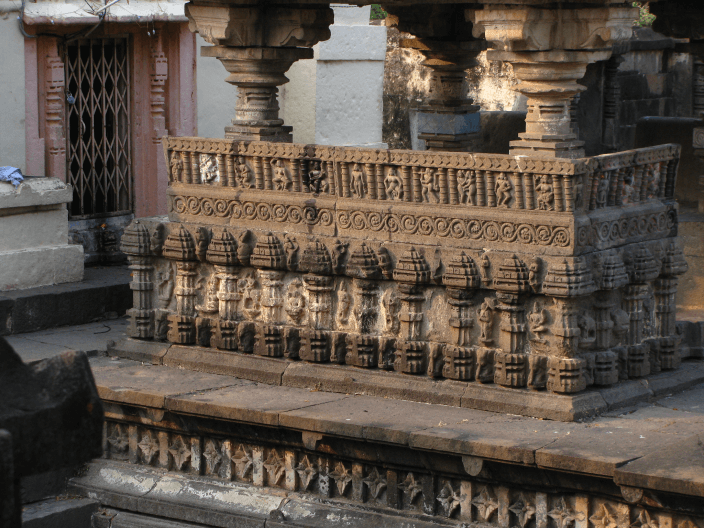

This barav is square-shaped with sides measuring 21 m at top and 14 m at the bottom, containing a series of steps carved in basalt rock. The entrance to the barav is from the southern side from where one descends down a few steps to reach the intermediate landing. The barav stands out because of its parapet wall which contains attractive devkoshta (niches) and a mandap (pavillion).

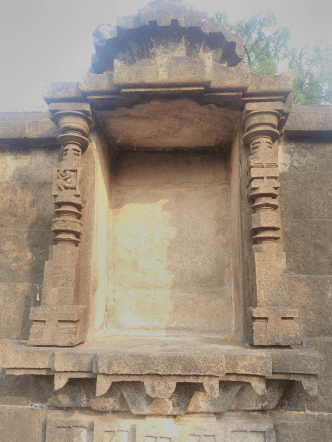

The two-metre high parapet wall of the barav acts as a kind of threshold, separating terrain and water. It contains 24 attractive devkoshtas forming a rhythmic pattern. Once upon a time, they housed idols of Vishnu in different forms. They reminded people about the sacredness of baravs and discouraged them from indulging in any acts that would pollute their water. Such kind of architectural detailing highlights the effective use of religious and spiritual ideas to encourage the water management practices of health and hygiene amongst people.

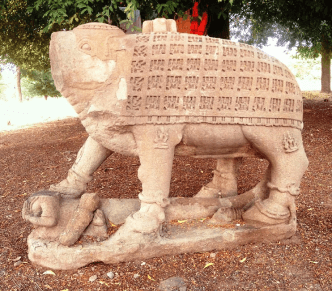

A square mandap with a roof supported by brackets resting on four circular pillars protrudes into the barav from its western side. Since the mandap was located outside the Vishnu temple, it is believed to once contain the idol of Varaha – one of the incarnations of Vishnu having the head of a wild boar and the body of a man. The remains of this idol can be seen today beneath a tree next to the barav. Apart from housing the idol, the mandap has a seating platform for people to relax and reflect in the presence of water. The external surface of the mandap is divided into panels by columnar motifs. The panels contain figurative motifs depicting the different incarnations of Vishnu and scenes from the Ramayana.

Despite the structural differences between the baravs at Manchar and Loni Bhapkar, both of them share some commonalities. Firstly, apart from minor structural damages, and wear and tear, both the baravs are in reasonably good conditions even after 600 years. They are fed by an ample quantity of safe groundwater even today. These facts demonstrate the engineering skills and hydrogeological knowledge of the people who built these baravs. Secondly, both the baravs are taken care of by their respective local communities. For instance, in 2019, few men from Manchar volunteered for cleaning and desilting the barav, as told by one of the volunteers Mr. Dhanesh Raut. He also said that every year during Diwali they light oil lamps on the steps of the barav.

Conclusion

In addition to the two baravs discussed in this photo-essay, there exist few others in and around Pune. However, most of them are in a ruined condition. Today, the usefulness of baravs as water storage structures may have declined due to relatively easy access to tap water. Despite this fact, we cannot neglect their value and turn them into places for dumping waste. We need to understand that baravs are much more than mere water storage structures. They have heritage value and have once served as community spaces with socio-cultural and socio-technical identity. Most importantly baravs connect people to water by enabling them to see, hear and touch water.

Currently, when water is increasingly seen as a commodity to be exploited to the fullest, protecting baravs becomes essential as they manifest our ancient cultural values of respecting, sharing and using water with utmost care, which is a precious gift from nature to humankind.

References

- Dandawate, P.P.; Joshi, P.S. and Gajul, B.S. 2006. Traditional systems of water management in Maharashtra. In Chakravarty, K.K.; Badam, G.L. and Paranjpye, V. (Eds), Traditional Water Management Systems of India, pp. 3–7. Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sanghrahalay, Aryan Books International. Bhopal, New Delhi.

- Mandake, G. (Ed). 2003. Man͂car yethīl ī.sa. 1344 madhīl shilalekha. In Shodha nibandha saṇgraha. Akhila Mahārāṣṭra Ithihās Pariṣad. Adhives̍an Akrāve. 2002-03. Chāndvaḍa.

- Marathe, M. 2019. Reimagining water infrastructure in its cultural specificity. Case of Pune. Technical University Darmstadt. urn:nbn:de:tuda-tuprints-92810

- Marathe, M. 2021. Baravas: An architectural exploration of the traditional groundwater storage structures of Pune, India. Ancient Asia. 12:1, pp. 1-1. DOI

- Pāṭhaka, A. 2017. Mahārāṣṭrātīl bārava sthāpatya āni pāramparik jalvyavasthāpan. Aparānt. Pụne.

- Raut, D. 2022. Photograph and video of barav at Manchar.