Introduction

In July 2019, a report on Pune’s aquifers, the first of its kind, was published by the Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM). The findings of the report indicated that the city could be headed for a groundwater crisis which could result in severe water shortages soon. This was alarming because the report also stated that half the city’s urban population is dependent on groundwater which constitutes half of the total water supply in the city.

In the same year, in September, Pune witnessed disastrous flash floods due to incessant rains that lasted for three days and left the city paralyzed. The impact of this flooding was a lot more severe than previous years. In fact in the last decade the episodes of flooding in the city have been on the rise. According to a recent study by A. Singh, J. Monteiro and B.K. Thomas (2020), the rainfall pattern for the past four decades shows that there will be an increase in the future incidence of disruptive floods in Pune as there will be more events of heavy rainfall in a short span of time.

This is the Pune Paradox. While too much water over the ground disrupts life, there is also too little groundwater to sustain an urban growth in the long run.

In this story, we try to explore the linkages between flooding and the depletion of groundwater levels. Why is it that the city which lies in a watershed area formed by a network of rivers and streams is headed for a water crisis? Why is it that a city that is naturally not prone to flooding experiencing severe floods? We also revisit some major experiences of floods to remind ourselves that every flood is man-made, caused by the disruptive forces of unsustainable living.

Know where we live…

Know how we live…

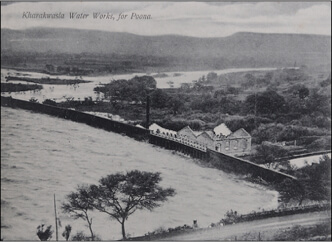

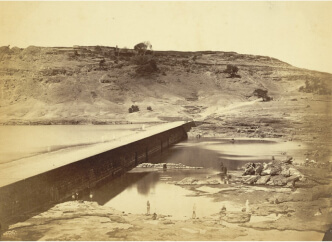

The early systematic urban expansion of Pune happened in the first half of the 18th century when the Peshwas relocated to Pune, established organized settlements, and provided people with water which was supplied by a network of aqueducts, wells, and tanks. Later, under British rule, around the early 19th century, the city expanded further and more public and private initiatives were undertaken to augment the water supply and control flooding on Mula and Mutha Rivers.

The deluge of 1961

By the 1950s almost all houses in the Pune Municipal area had piped water supply, but it was inadequate for the growing demands of an expanding city. Therefore, in 1957, construction of a new dam on Panshet, a tributary of the Mutha River, was initiated.

Even before the Panshet dam was ready and much before its scheduled opening, water was impounded. For two days thereafter, the officials remained aware of having dangerously risked the tenacity of the structure but did little to avoid a disaster.

Eventually, as was feared, on the morning of July 12, 1961 the dam burst and within three hours vast areas in the city, along the banks of the Mutha River, were ravaged by the flood waters.

The people in the city were caught completely unaware. The water levels remained high for six hours causing tremendous destruction of property and lives.

An official account mentions extensive damage and destruction of lives and property. The deluge created a major economic and housing crisis in the city.

2,500

Structures damaged

26,000

Families SUFFERED

10,000

Families became homeless

The draining of dams affected the drinking water supply in the city. People were then forced to depend on water from the existing wells that were mostly fed by the waters from natural streams. To make it easy for people to find water, many houses with wells were deliberately marked. Today, some houses continue to have ‘WELL’ marked on them.

Here are first-hand accounts of the aftermath of 1961 flood.

The post-flood resettlement

The post-flood resettlement activities created new suburban areas where thousands of families that had become homeless overnight were provided with shelter homes. The people who for several generations had lived in proximity to the river, were now moved away from it.

Among the areas that emerged because of the floods are today’s Sahakar Nagar and Navi Peth. In the Navi Peth, between today’s Mhatre bridge and Shastri road, is an area known as the ‘Senadatta Peth’ (The name ‘Senadatta’ translates in marathi as “given by the army”). It is here that the Indian Army that was called to help with the post-flood rehabilitation programme, built hundreds of half-cylindrical structures called Nissen Huts as shelter camps.

Mr. Mahesh Jangam, a resident of Pune, documented these Nissen Huts, to preserve the memories of the flood. While some of these huts can be seen even today, many have become permanent housing societies although for nearly six decades its residents lived as tenants. In 2019 the state government finally granted the ownership rights to as many as 103 housing societies in the Gokhalenagar, Lokmanyanagar, Sahakarnagar, Erandwane, Parvati Darshan, Dattawadi, Shiv Darshan, Nissenahat and Bhavani Peth areas giving the rehabilitated people a sense of closure.

A report published by the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, in 1967, states that 196 families were moved to these huts by November 1961. It further describes these measures as “most expensive and wasteful” due to their high capital cost and low residential density.

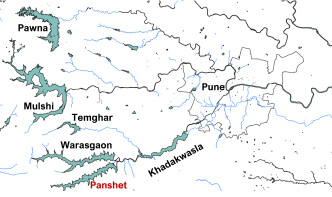

The Panshet flood is a reminder that dams are human interventions and although they regulate and control floods, dams can also cause catastrophic floods that are sudden and have a lasting impact on people’s lives! The possibility of a devastating flood due to a dam burst in and around Pune is a real one as the city, which is in the plains on the downstream of major rivers, is surrounded by dams – Pawna dam, Mulshi dam, Temghar dam, Warasgaon dam, Panshet dam and Khadakwasla dam. The 2015 disaster management plan of Pune Municipal Corporation recognizes this fact and identifies Khadakwasla dam to be the most dangerous in terms of its potential impact.

Today the population of the Pune metropolitan area is nearly ten times more than what it was in 1961! Although there hasn’t been any dam burst after the great deluge, the episodes of flooding have been on the rise. In the following sections we see the types of floods experienced by the city in recent times.

Floods caused by release of waters from the dams

In the case of heavy rainfall in the catchment areas the dams around Pune are forced to release their waters, the rivers swell and inundate the areas adjoining the banks. The Pune Municipal Corporation and Irrigation Department then issue prior flood warnings and alert citizens to evacuate from low-lying areas near the river to safer places. Many gather on the different bridges to watch the sight of the river which swells and flows like it would have in its natural form.

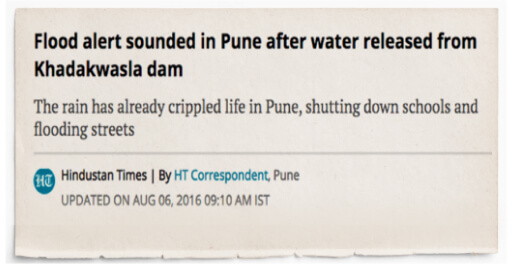

In August 2016, the Irrigation department in Pune issued a flood alert and released waters from the Khadakwasla dam. It was the highest discharge of the monsoon season in that year. Below are some of the images of the flood.

While the sight of the Mutha river flowing in its natural form may have been a sight to behold, the post flood face of the city looked the opposite. As the water receded tons of plastic waste and a thick layer of silt and mud accumulated along the river banks.

Urban Floods

Urban floods result from heavy rainfall that leads to severe waterlogging and flooding within the city which disrupts civic life and causes damage to personal life and property. Such floods are directly linked to haphazard urban growth. In this section, we look at some of the causes of urban flooding.

Urban Floods: Causes

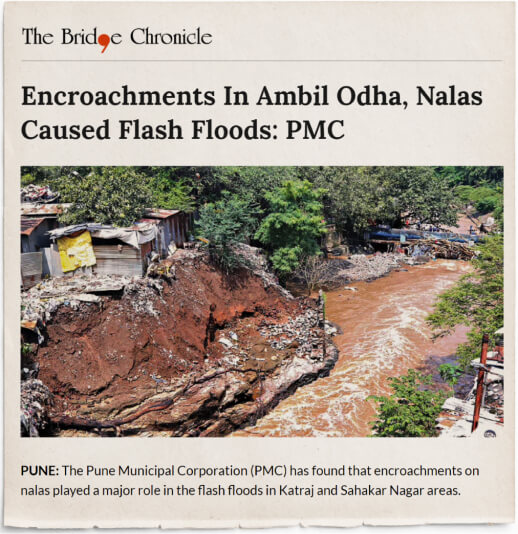

Rampant encroachments, dumping of construction debris and concretization: The case of Ambil Odha.

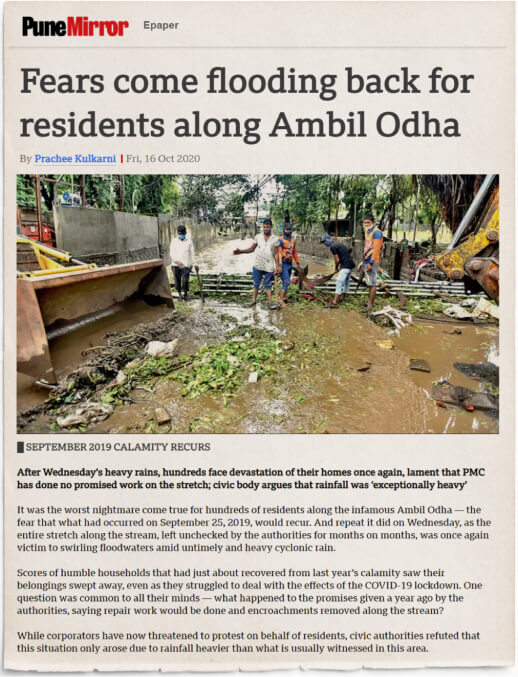

Among the major causes of flooding is the dumping of construction debris and rampant encroachments along the river banks and on the natural streams that leads to the blocking of natural drainage channels and increased concretization of surfaces rendering them impervious. The case of Ambil Odha is an example of this.

Ambil Odha is a natural stream that originates in the Katraj hills and flows northwards through the densely populated city to drain into the Mutha river. Along its way it feeds the Katraj lake and the lake inside the Rajiv Gandhi Zoological Park. It also feeds several wells and water tanks in the historic areas of the city.

The Ambil Odha sub-watershed area is characterized by variable gradients such that there are steep to moderate slopes in different parts along the stream. The rainwater gushes at a great speed in some areas while it flows in a controlled manner in other sections. The area adjoining the stream is heavily built and rampantly encroached upon. Mining activities in the banks have also been reported. Besides this cutting of hills in the Katraj area has altered the natural course of the stream. All this has resulted in the increased vulnerability of the population living in the low-lying areas which suffered immensely during the severe floods in 2019. The experience of the flood led to a highly controversial anti-encroachment drive in 2021.

Channelization of river

The other important causes of flooding are the channelization of rivers, particularly by concrete walls that not only affect the natural flow of water but also create stagnant pools of dirty water that tend to block the natural streams. Below is the image of Mutha River bank from 1986. Notice the width of the channel and the natural gradient along the bank.

Present condition of Mutha River & its banks

The rivers in the city are heavily polluted mainly due to the draining of untreated sewage water into it. A small measure of the extent of river pollution in a matter of five decades can be seen in the image below. The image shows the kind of garbage deposited by the river on the banks after the two floods, most of it being plastic waste.

Glimpses of recent urban floods in Pune

In 2005 when incessant rains from a major cloudburst caused unprecedented floods in Mumbai, Pune too experienced severe flooding due to the overflowing Pavana and Mula Rivers. The Pimpri-Chinchwad industrial areas were the most affected.

Before & After pictures of 2005 floods

2019 Floods

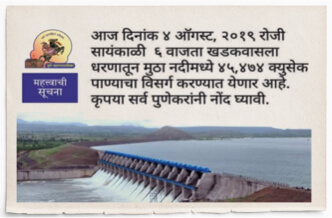

In 2019, intense rainfall over three days left the city paralysed as there were two major flooding episodes. The city received close to 60 mm rainfall in 36 hours from August 3rd. The combined effect of heavy rains and water released from the dams led to severe waterlogging and flooding in many parts of the city. The Fire Brigade and National Disaster Response Force had to be deployed to evacuate people to schools, temples, and community halls in safer areas. Some also took refuge with friends and families living in other parts of the city.

Before & After pictures of 2019 Floods

(Photo source: before flood picture by Prajakta Divekar, flood photo by Jeevitnadi)

Every flood leaves behind, in varying degrees, a trail of destruction of property and lives. It does long-term damage to the sense of safety and wellbeing of those affected by it. While some may recover their losses sooner or later, others must rebuild and start all over again.

The story of Baner and Pashan areas

It is only in the past decade that urban floods have become a cause of public concern in Pune. Adaptation strategies are slowly but surely evolving, mainly through the initiatives of civil society and citizen activism. It is their efforts that are successfully rendering visibility to the connections between urban flooding and the groundwater situation. In this regard, the story of two rapidly urbanizing areas, Baner and Pashan, can provide interesting insights.

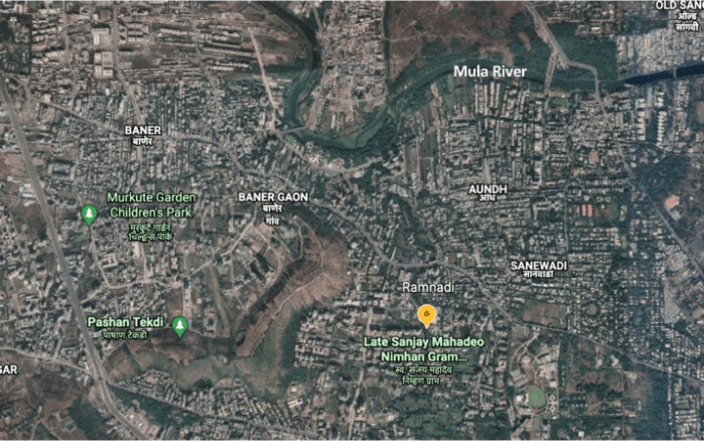

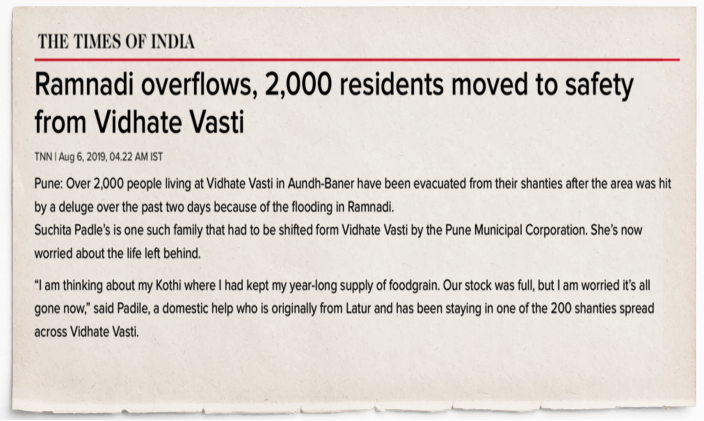

Baner and Pashan areas are some of the most rapidly urbanizing areas within Pune. One of the defining features of these areas is the Baner-Pashan hill complex which is a large urban recharge zone, part of the Ramnadi sub-watershed area. Ramnadi, one of the tributaries of the Mula, flows through the developing suburbs of Bavdhan, Pashan, Baner and Aundh. It feeds two lakes – the Pashan Lake, built by the British; and the Manas Lake built in 1977. These lakes provide water supply to the surrounding villages. Studies show that the 19.2 km long Ramnadi has, over a period, lost over one-fourth of its natural streams and 15 percent of its width to the construction projects in the area.

In recent times, the Ramnadi has come under severe stress and its water carrying capacity reduced due to factors such as, the dumping of debris from construction activities and pollution due to the release of untreated sewage into the river. On 4th October, 2010, a cloudburst caused intense rainfall that resulted in severe flooding in the Kothrud, Bavdhan and Pashan areas. Soon after, a group of concerned citizens demanded the removal of encroachments along the Ramnadi, and in March 2011 they successfully protested the construction of a retaining wall in the river by a private company.

In 2019, the residents of these areas along with non-governmental organizations set out on a mission to restore the Ramnadi and control its disruptive flooding by the year 2020. But, in the same year the river raged once again flooding the surrounding areas. The efforts, however, are on to meet the objectives of the mission and a report was published that identified the causes of flooding on Ramnadi and made recommendations for government interventions.

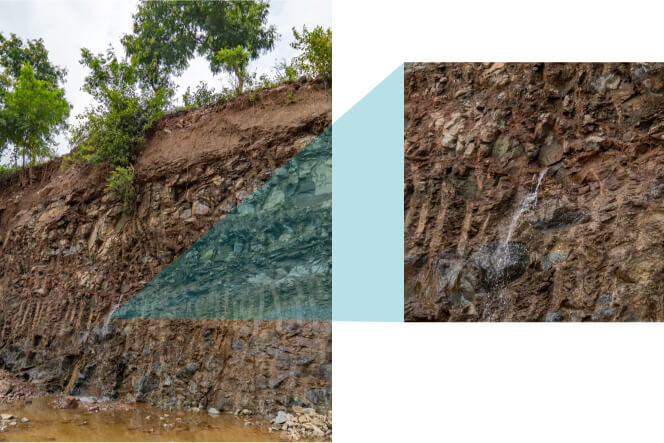

Many housing societies in and around Baner and Pashan areas are facing water scarcity despite having borewells. Several large housing projects and road widening activities, among other reasons, are systematically excavating the hills in the area and damaging its aquifers. The on-going construction activities for a four-lane highway there has also exposed the aquifers.

As the aquifers dry up, the source of water for the trees whose root goes deep also disappears. Gradually, with the depletion of groundwater the tree cover will disappear. Trees hold soil and water thus play an important role in flood control.

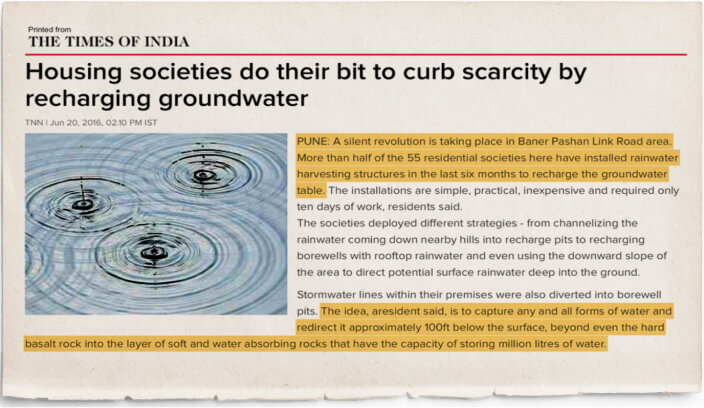

Notice in the images the water gushing out of a damaged aquifer. These aquifers have now dried up and no attempt was made to divert or collect its waters. This is the plight all over the city where urban aquifers are being destroyed either by unregulated extraction of groundwater through borewells, or mostly for the construction purposes.

Realizing the depleting groundwater levels, some of the resident welfare organizations in the Baner and Pashan suburbs are encouraging housing societies to take simple, cost-effective measures to recharge groundwater. Where such activities are undertaken, citizens have observed that while groundwater levels improved, the incidence of flooding in their premises also reduced.

While some may argue that change in a city is constant, our attempt here has been to show that the pace of change is not constant. The paradoxical relationship that residents of Pune have with water today is the result of the unprecedented pace at which the city is transforming along a faulty model of development that is rendering the city increasingly unsustainable. Amidst this, the adaptive mechanisms adopted by the citizens and civil society, such as groundwater recharging, offer the opportunity for a creative reconciliation between human interventions and nature. There is a need for these efforts to be augmented and supported through government policies and programmes.

References

- ACWADAM (2019). Report on Pune’s Aquifers: Some Early Insights From a Strategic Hydrogeological Appraisal www.researchgate.net

- Reference india.mongabay.com

- S. Brahme and P. Gole (1967), Deluge in Poona: Aftermath and Rehabilitation Report. No.51, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

- Shinde, Kiran A.(2017). Disruption, resilience and vernacular heritage in an Indian city. Urban Studies, February 2017, Vol 54, No.2, pp 382-398. www.researchgate.net

- Gabale, Shrikant M. (2016). Impact of urbanization on geomorphic environment of Pune and surrounding hdl.handle.net

- Pune City Floods: Causes, Analysis and Mitigation Measures Report, 2021 www.ecological-society.com

- Pune Municipal Corporation Report (2017). Pune River Rejuvenation Project: Draft Master Plan www.pmc.gov.in