Introduction

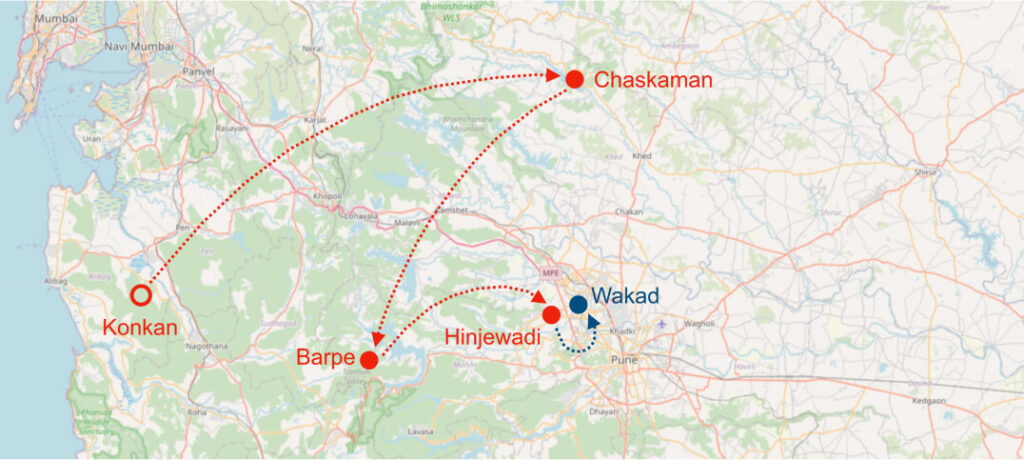

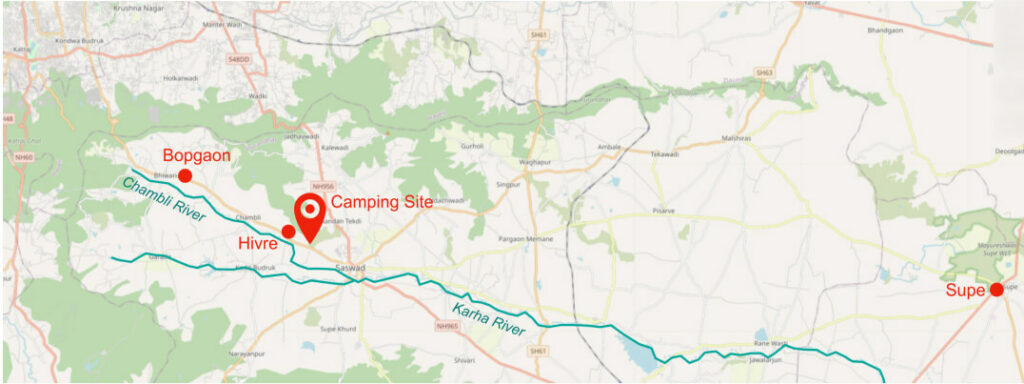

Many generations ago, pastoral communities moved along the hills, streams, and flowing water bodies in the Deccan plateau and beyond. This story is about these pastoral communities, their rustic deities, and cultural landscapes. “This landscape was a result of the movement of these communities in search of water and fodder, as well as their corresponding geographical situation: the seasonal movement from the wetter Western Ghats to the drier eastern parts of Maharashtra and beyond. This formed the communities’ early movement patterns. The hills of Pune were an integral part of those seasonal movements.

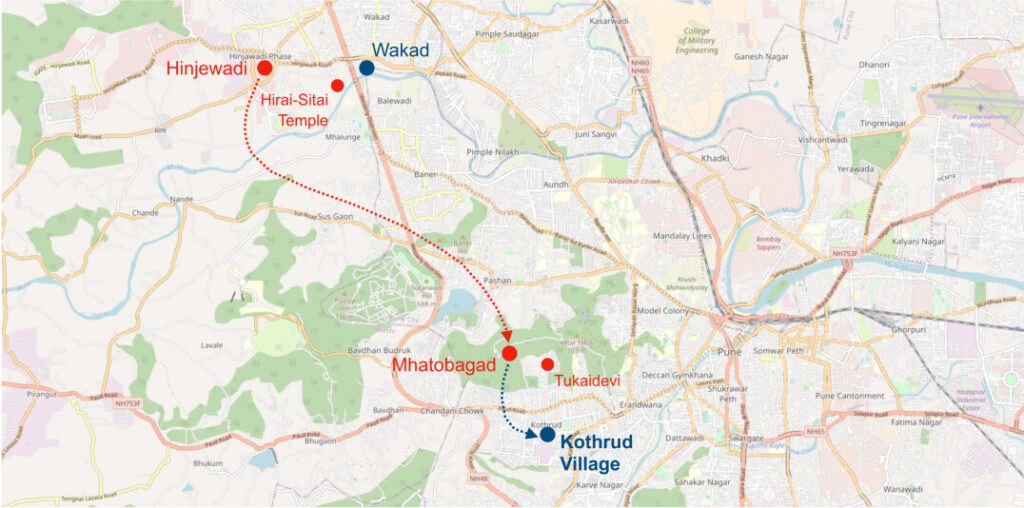

The hills of Pune are a crucial component of the freshwater cycle as receivers of rainwater recharging the aquifers leading to an elaborate stream network feeding into the rivers of Pune. The hills of Pune still hold the memories of those seasonal movement patterns by the pastoral communities such as dhangars (shepherds), gawalis (cattle grazers), katkarisKatkari is a forest tribe in Western Maharashtra. Today, katkaris are also located in the riverine belts for freshwater fishing.

(forest tribes), kolis (fishermen), bhois (fishermen) and their rustic deities such as Vetal, Mhasoba, Tukai, Sati Asara, Bhivai and Dhuloba.

This story talks about the association of pastoral communities with the environment through their livelihood practices, folklores, mythological tales and rituals, thereby throwing light on the ecological wisdom of these communities. The story is presented as a constellation of micro-stories anchored around the rustic deities of the hills (hill landsHill lands refers to “hills” that have steep and/or gentle gradients.) and of the lower lap of these hills (lap landsLap lands refers to flat terrain, extremely gentle slopes starting from foot of the hills, and plateaus.), and their encounters.

The story continues…

In all the above cases, the connections between far flung places have been forged primarily through the movements of pastoral communities and encoded in their stories, images, and figurations.

But a case of Sati Asara at Bavdhan in Pune offers a different narrative altogether as an indicator of changing imaginations implied through deities, communities, and geography. This Sati Asara resides in the premise of Dada Marathe’s residence, a migrant from Nimgaon in Solapur. The story of Sati Asara begins at Nimgaon when Dada Marathe’s uncle Tatyaba Marathe went missing and emerged from a nearby well with the Sati Asara. His family believed that it was the Sati Asara who brought him back, so the family started worshipping her. Dada Marathe’s father Sayaji Marathe continued the tradition of worship started by his uncle. Thereon, in his family, all auspicious prenuptials began with cooking in water from the River Bhima – “jal aanane”, now from a nearby well, for convenience. The food is first given to seven kumaris (unmarried young women) before feeding the villagers. When Dada Marathe migrated to Pune for livelihood reasons, the goddess moved with him. His devotion now connects Nimgaon and Pune. This story illustrates the connections between different places through the love of the founding devotee for a deity.

Concluding remark

These stories of pastoral communities and their rustic deities in hill lands and lap lands speak to how “places” get imagined, revered and connected into a melting pot of geography, culture and mythology. These rustic deities provided an emotional anchor in an otherwise hostile environment encountered during seasonal movements. Further, these deities which are now getting lost to urbanisation, are potential links to trace our lost water in its tangibility and intangibility as imagined by the pastoral communities, and their ecological wisdom.

References

- Feldhaus, A. 2003. Connected Places – Religion, Pilgrimage and Geographical Imagination in India. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Glushkova, I., and Feldhaus, A.1998. Goddesses and Domestic Realm in Maharashtra. Pp.73-81 in Glushkova, I., and Feldhaus, A. (eds.): House and Home in Maharashtra. Oxford University Press, Delhi.

- Gunther-Dietz Sontheimer. 1989. Pastoral Deities in Western India. Oxford University Press, New York, 276.

- Kosambi D.D., 1962. Myth and Reality – Studies in the Formation of Indian Society. Popular Prakashan, Bombay.