From a small contained riverside world to IT-Education hub of India

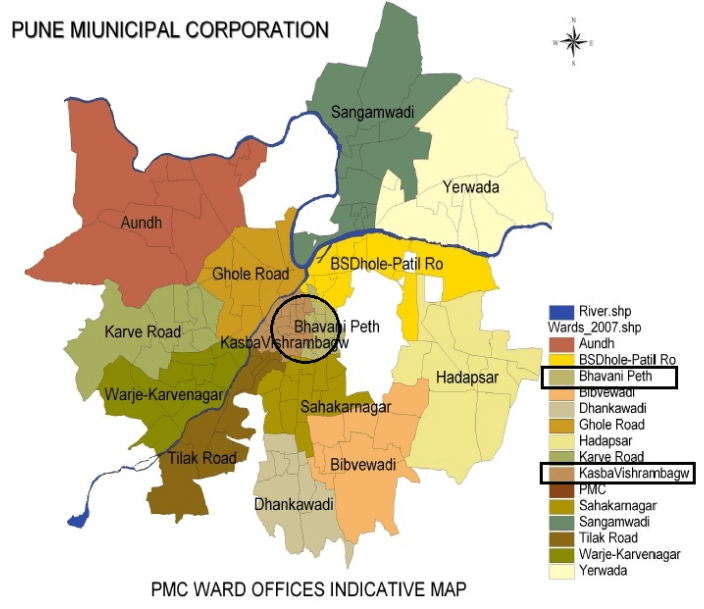

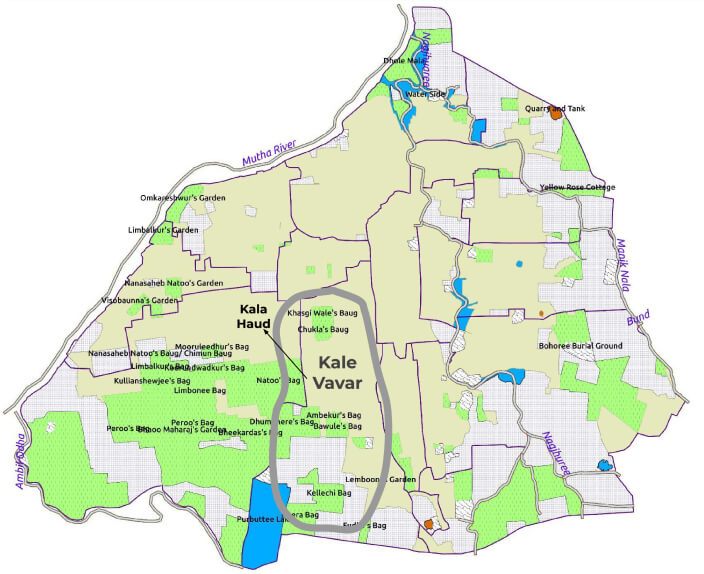

Pune, today, is known by its distinctive neighbourhoods like Baner, Pashan, Aundh, Deccan, Erandavane, Kondhva, Kharadi, Sahakarnagar, Dhankavadi and many more sprawling around the confluence of the Mula-Mutha Rivers.

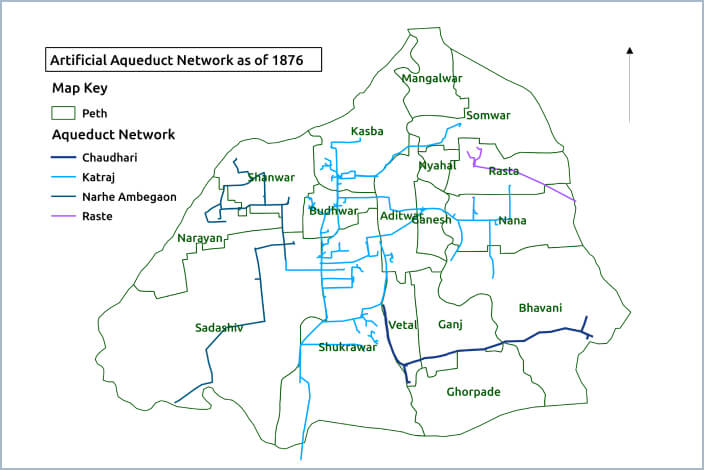

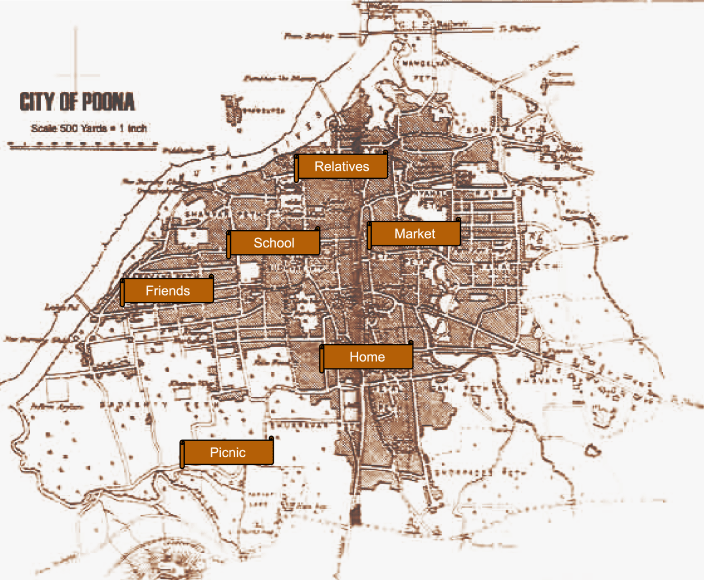

As a school girl in the 1980s-90s, Pune for me laid in Peths – the contemporary wards or neighbourhoods which have been in existence since the Peshwa’s time or some even before that. Home in Shukrawar Peth, school in Sadashiv Peth, friends in Shanwar Peth, relatives in Narayan Peth, shopping in Ravivar Peth and weekend morning climbs at Parvati! Life was simple. In this small world, A letter from anywhere in the world could easily reach my Shukrawar Peth house on a single address line – Opposite Kala Haud!

My first encounter with what is today’s most valued heritage of Pune!

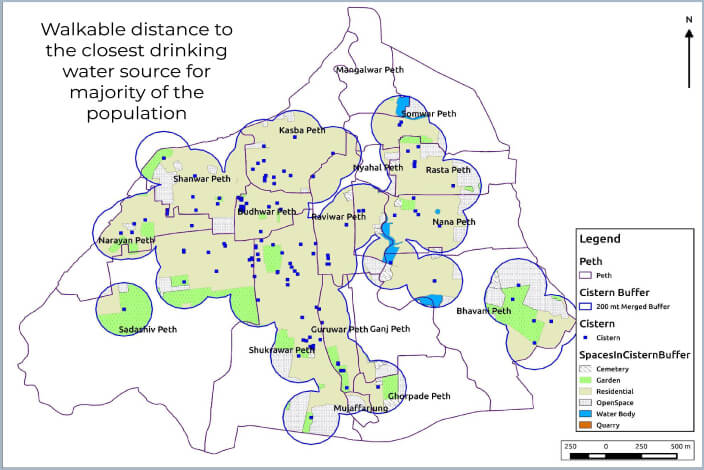

I remember that every summer the Pune Municipal Corporation would begin regular water-cuts and water shortage was a routine. As a kid, I enjoyed it because I used to get a chance to go across the street, fetch a few buckets of water with the help of our maid and get a peep into a mysterious small cistern, called the Kala Haud. It almost felt like magic when I could look down from this just 2ft by 2ft opening, I could see clean water few meters deep, flowing almost parallel to the traffic on the road.

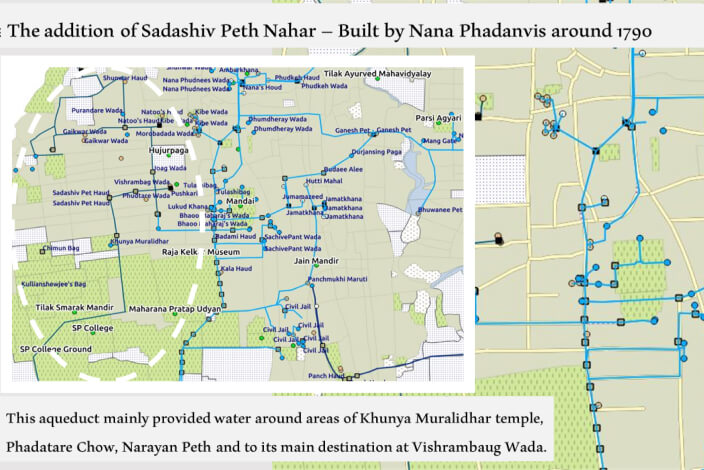

I indulged again in this ‘proud memory’ from my childhood to figure out what it was and how it worked, this time as an academic exercise. The cistern acquired its name from Kale Vavar – an open area identified as black due to the presence of black soil. This area was developed by Sardar Jivajipan Khasagiwale around 1730s and named as Shukrawar Peth. However, the cistern that I was so proud to fetch the water from, happened to be just a small maintenance shaft of the larger system, locally known as Uchchhwas or dipping well.

Unravelling the lost heritage – brining it to life through maps!

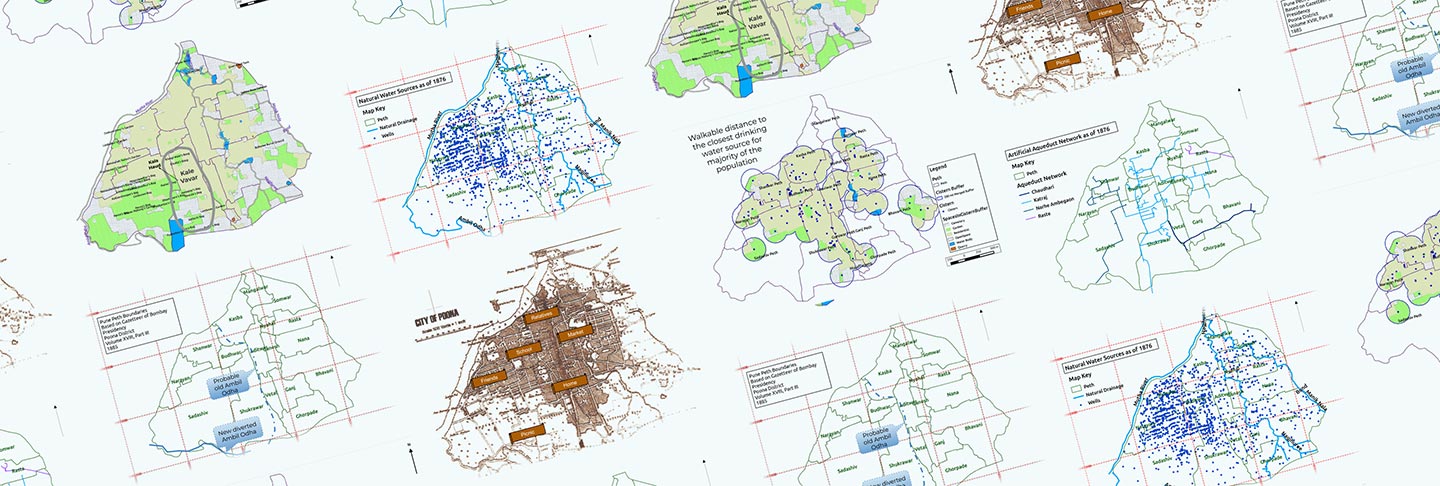

While digging into these intriguing stories of Pune’s water from the past, the geographer in me took over the steering of this journey! While navigating through Pune’s Peshwa era, the maps became my resources, recipes, routine and results! Here are a few glimpses.

The origins – Pre-Peshwa Pune

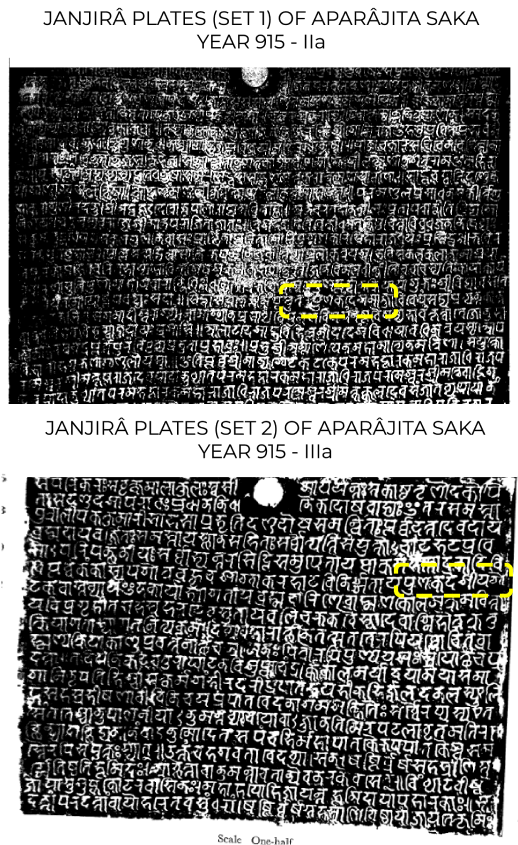

Pune, today’s second largest city in Maharashtra, was a small village on the confluence of Mula-Mutha Rivers. Archaeological evidence locates this settlement in the Deccan since Satavahana period (~ 200 BCE to 200 CE). The 10th century CE copper plate of the Shilahar King Aparajit identifies Pune as ‘Punak Vishaya’, meaning ‘a place of prime importance’.

The Urban Pune

Peshwa, literally meaning a leader in Persian, was a designation assigned to the appointed Prime Minister of the Maratha Empire in the Deccan. Balaji Vishwanath Bhat was the first appointed Peshwa by Chhatrapati Shahu in the early 18th century. In 1719-1720, Bajirao Ballal, son of Balaji Vishwanath and popularly known as Peshwa Bajirao 1st obtained the title Peshwa from Chatrapati Shahu Maharaj. Around 1728, he moved his base from Saswad and developed Pune as the capital of the Maratha Empire in the early 18th century. Pune evolved as a centre of power thereafter.

The beginning of modern urban thought, in terms of providing basic civic facilities to the citizens, is seen through the acts of the visionary Balaji Bajirao, also known as Nanasaheb Peshwa during the second half of the 18th century. The historic drinking water supply system of Pune is a glorious example of intricate planning and execution in historic times.

What is a Qanat and how it comes to Pune?

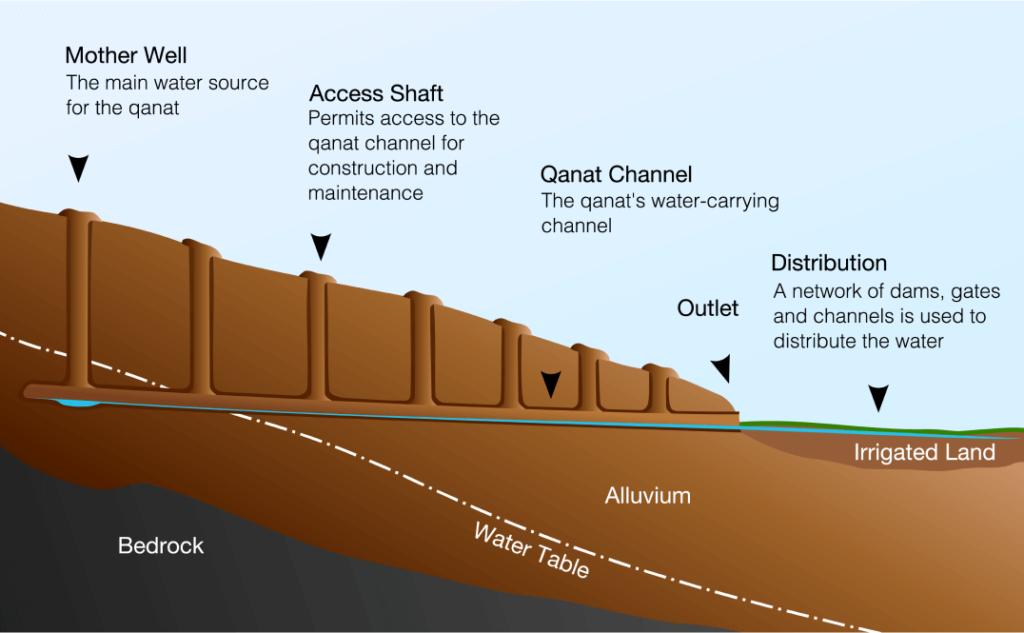

Karez or Qanat or Nahar are the underground channels which connect the subterranean water from the aquifers or wells. This water is then made available on the surface by tapping into those channels. This tradition seems to traverse the path from Persia to India via Afghanistan and Baluchistan areas. The system is also provided with shafts at intervals for maintenance purpose. These systems have been adapted in different territories according to the geographic conditions and regional needs.

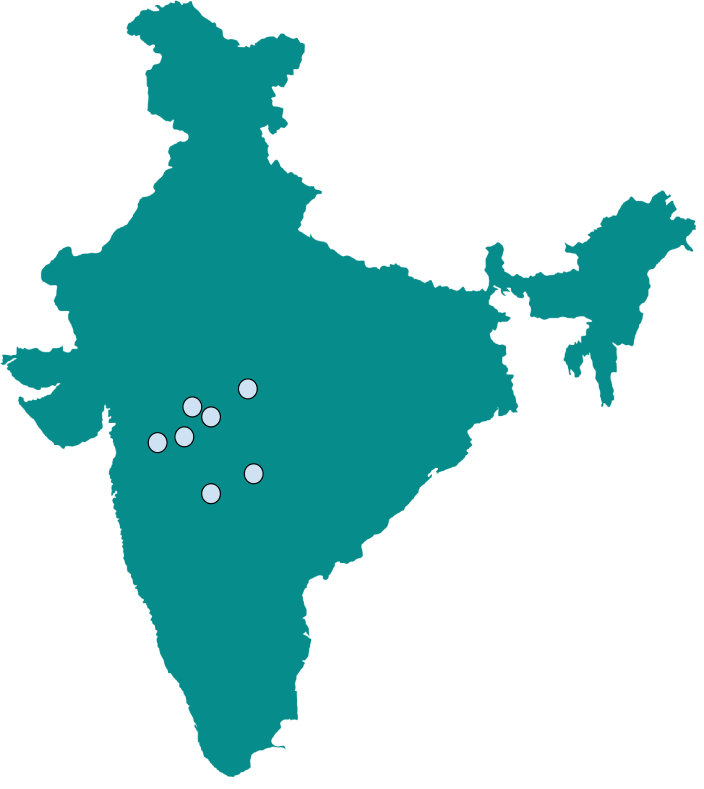

In the Indian subcontinent, the important change in terms of water distribution which occurred due to the advent of the Sultanate was that the water was brought to habitations instead of settlements being situated near water. In medieval India, we see the beginning of these changes done mostly during Mughal rule. The Karez or Qanat systems are seen in historic Indian cities such as Bijapur, Ahmednagar, Daulatabad, Aurangabad, Burhanpur, Bidar and Pune. These are predominantly Sultanate ruled areas. While the work on Pune aqueducts was to begin, the systems in Aurangabad and Ahmednagar, respectively built by Malik Ambar and under the Nijamshahi rule were completing more than a century of successful service. The water was sourced from wells in these cases. A system in Burhanpur, from around the same time, was designed by a Persian scholar by studying the groundwater recharge zone in a valley of the Satpuda ranges. The historic city of Pune is an example of regional adaptation and implementation of this system.

Locations of Indian cities with historic qanat systems

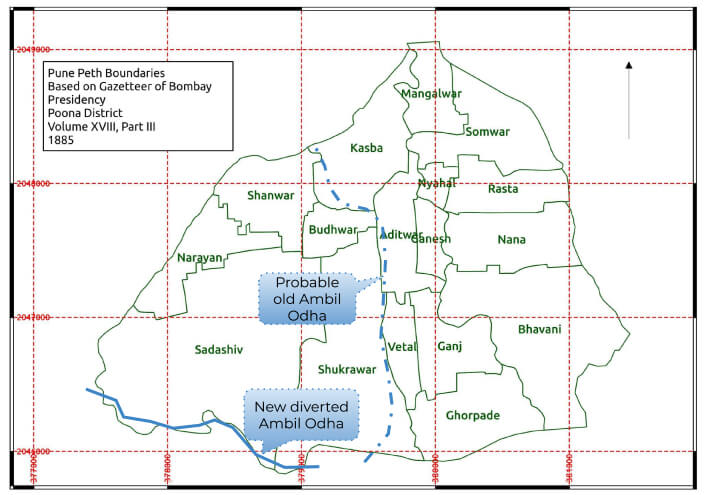

Diversion of Ambil Odha and the construction of the underground Nahar system

Though Pune was a climatically and politically ideal location for the Peshwa’s capital, it was soon realised that frequent flooding of Ambil Odha, a rivulet flowing from Katraj hills towards the north and confluencing with the Mutha River, was creating havoc in the settlements along its banks. The course of this rivulet was diverted probably sometime in 18th century.

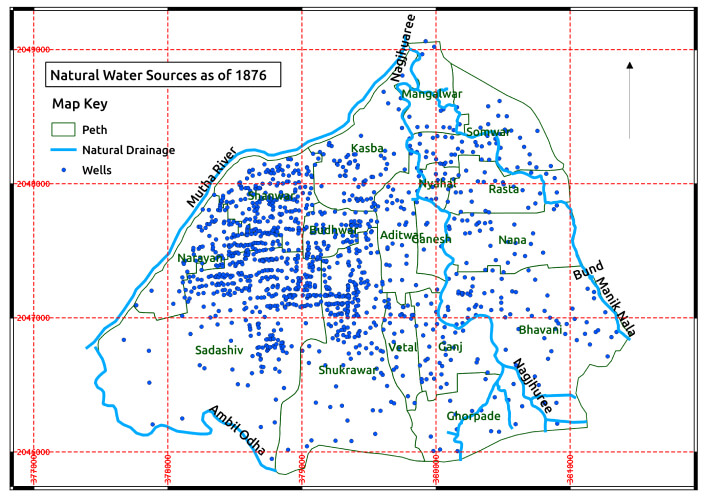

On the contrary, with respect to the availability of potable water, though there were many wells, the number of perennial potable water wells was very small. The majority had brackish or saline water. As per a record in Pune Nagar Samshodhan Vrutta, as of 1864 (almost a century after the initiation of the aqueduct system), out of more than 1500 wells, less than 100 were of potable water. The 1885 administrative record also supports this information.

The birth of the system

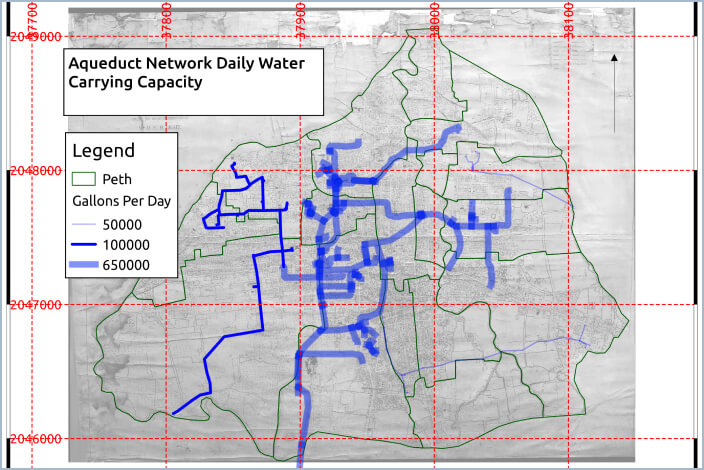

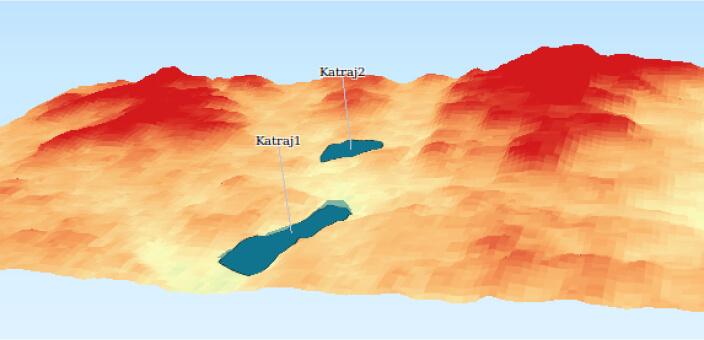

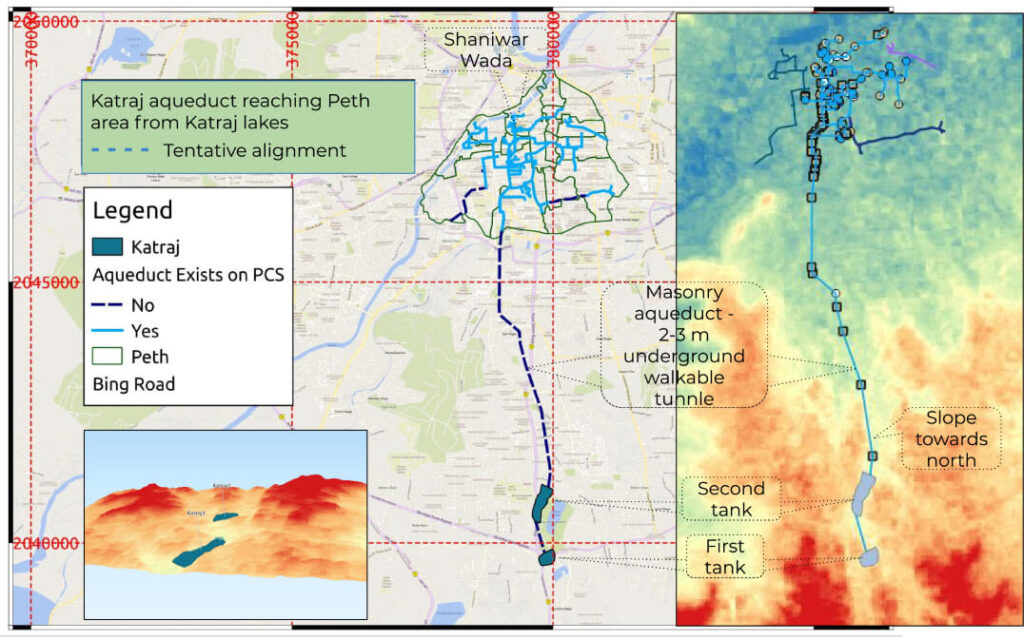

In 1750, Nanasaheb Peshwa initiated the construction of two stone masonry dams at Katraj, around 6 to 8 km south of the city. The dams accumulated rainwater runoff from the hill slopes and also had fresh water springs in their bed.

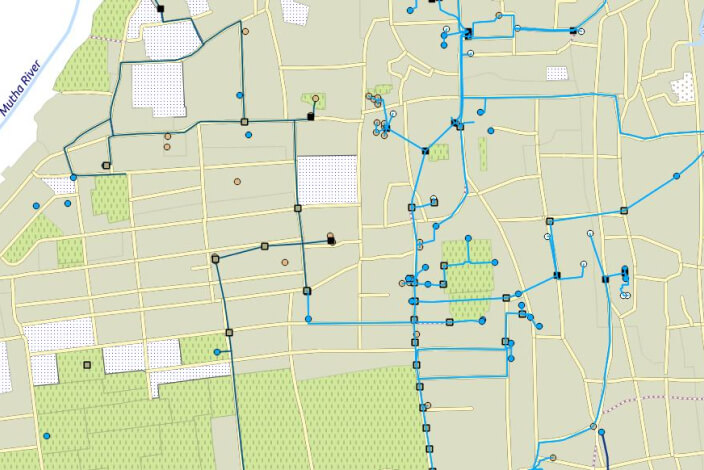

A gradual drop of about 100+ meters existed from the Katraj dams towards the north up to the Mutha River. Through surface runoff from the catchment and living springs, the water accumulated in the first tank. Allowing the silt to settle down, it flowed into the second tank. It was then carried into a masonry aqueduct, locally known as Nal/Nahar. The aqueduct, an arched tunnel was about 2 to 3 meters below ground level, measured around 80 cm in width and around 2 meters in height allowing a person to walk comfortably across its entire length. The water was brought into Shaniwar Wada, the residential palace and court of the Peshwas with excess water being carried to the Mutha River.

The system at its best!

This system is an impeccable example of urban planning and development. The foresightedness shown in planning and the execution in absence of modern-day technology is enthralling.

Interactive map of Pune’s historic water supply system

Present state of the system

Accelerated urbanisation over the last few decades has left many components of this historic water supply system either ignored or completely destroyed. This has thus rendered the system dysfunctional and abandoned. Despite it being in regular public use until the end of 20th century, there is no organised record maintained by the municipal corporation which could help document the usage of this system. We can thus rely only on recollecting the stories from the locals who were the consumers of this system.

References

- Bhagvat, S. & Bhagvat, R. Peshwekalin Panipuravatha Yojana (Marathi), – https://youtu.be/xldUKwTHGW8

- Gokhale, P. & Prof. Deo S. (2016). Digital Reconstruction and Visualisation of Peshwa period water system of Pune. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 4 : 2016 [ISSN 2347–5463]

- Gokhale, P. (Unpublished 2015-2016) Creation of GIS based digital map for Maratha period Pune – Historic GIS, research project for Saṁvidyā Institute of Cultural Studies, Pune-India

- Joglekar P. P., Deo S., Balkawade P., Rajaguru S. N., Deshpande-Mukherjee A. and Kulkarni A. N., (2006-07). A New Look at Ancient Pune through Salvage Archaeology (2004-2006). Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute Vol. 66-67, 211-225

- Karve C. G., (ed), (1943). Pune Nagar Samshodhan Vrutta. Vol 2-4. Pune: Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal

- Karve C. G., (1942). June Haud (Marathi), pp 14 in Karve C. G., (ed.), 1942. Pune Nagar Samshodhan Vrutta. Vol 1. Pune: Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal

- Light R. E. H., (1869-72). City of Poona. Poona.

- Mirashi, V. V., (1977). ‘Inscriptions of the Silaharas’ in Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, VI In: New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

- Poona City Survey, 1876.

- Pune Municipal Corporation, 2013. Draft Development Plan For Old Pune City (2007 – 2027) Published U/S 26(1) Of Mr and Tp Act 1966. Accessed online at Indiaenvironmentportal

- Pune Municipal Corporation, Revision Of Development Plan Sanctioned In 1987, As Tp1966 Section 38, Strategic Environmental Assessment Scoping Report. Accessed online here Pune Corporation

- Gazetteers of Bombay Presidency, Poona District, Volume XVIII, Part III, 1885.

- File:Insideqanat.JPG. (2021, November 25). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 05:40, January 7, 2022 from Wikimedia

- File:Qanat cross section.svg. (2021, January 29). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 05:40, January 7, 2022 from Wikimedia

- QGIS documentation accessed online at QGIS Documentation