“I, in rains that fall,

waters that travel through rocks,

flows that touch your feet.”

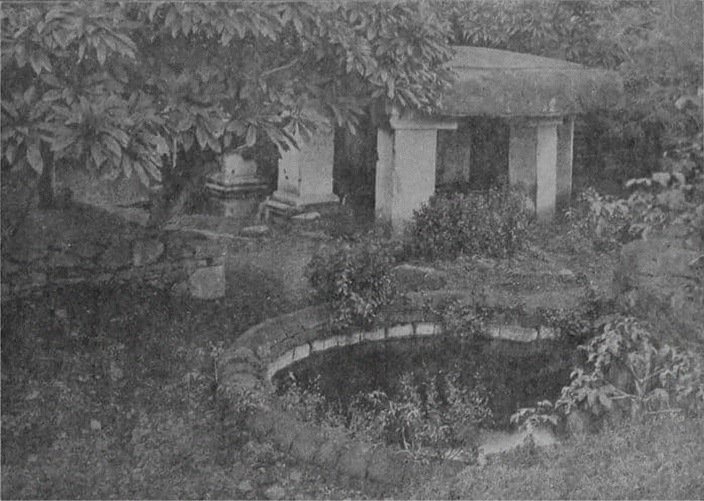

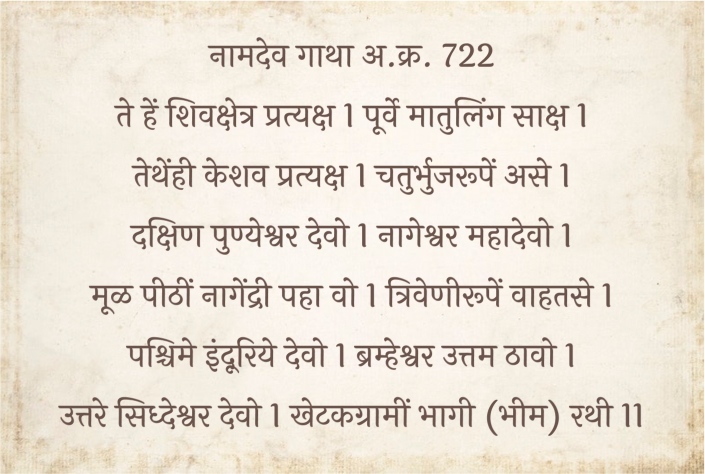

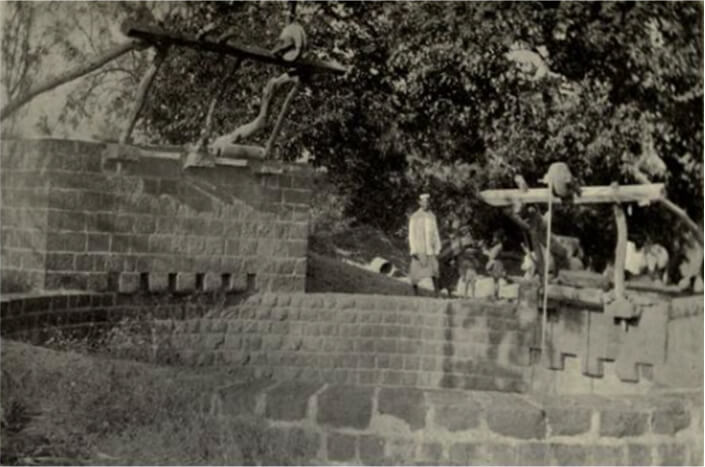

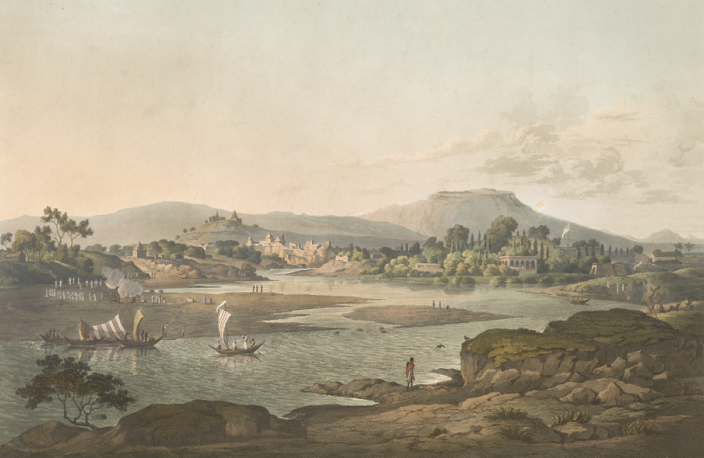

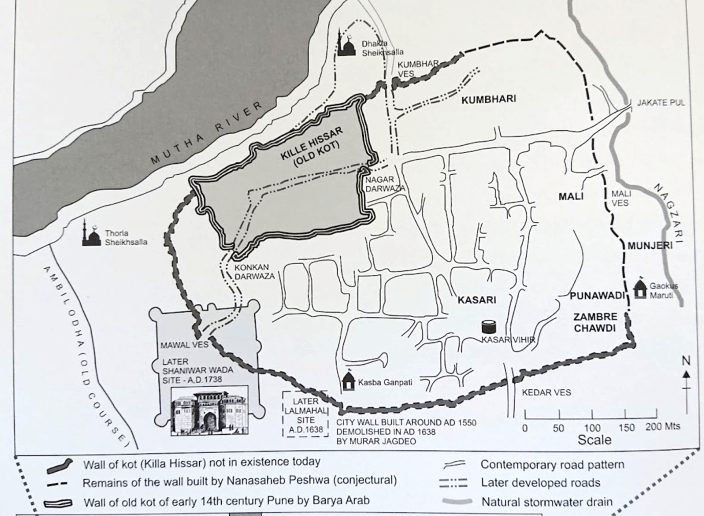

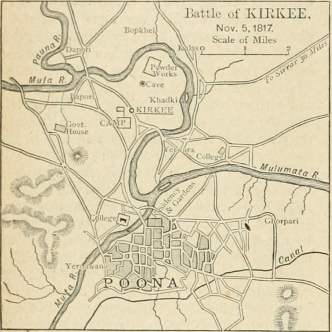

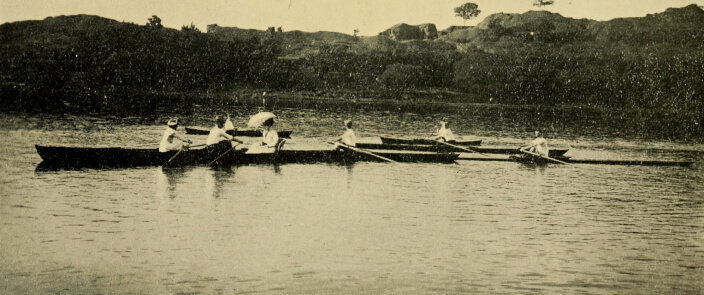

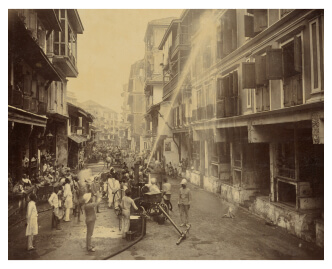

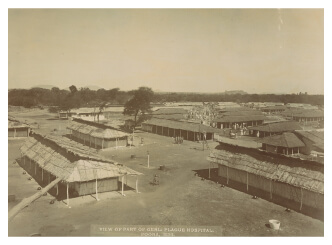

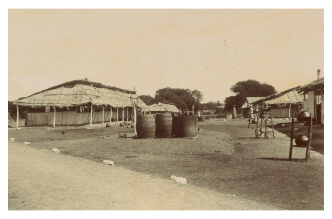

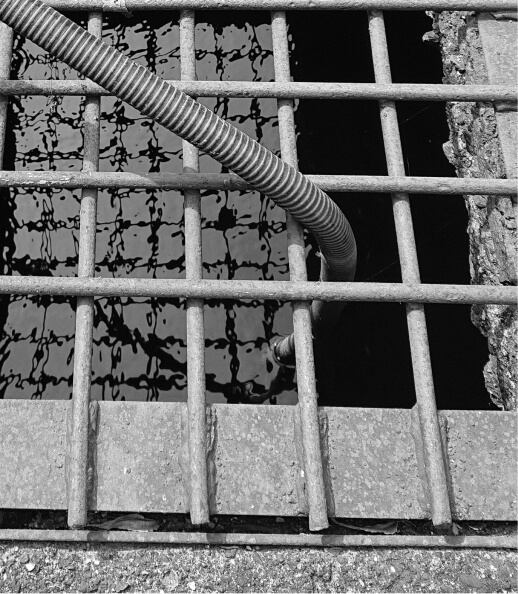

Water flows through Pune (erstwhile Poona) and its environs as rains, rivers, streams, canals, and aquifers. As Pune evolved from a hamlet to one of the largest cities in Maharashtra, water has been harnessed for drinking, washing, agriculture, and more. Through our heritage, both tangible and intangible, patrons, rulers, governments and technology have often altered the flows, the freedom, the paths of these waters –

Do I sit or flow,

Meander or piped in,

What will it be today?